Lessons from the Mountains

This blog introduces a short series about museums and heritage interpretation in the Alps. Lockdown has given me unexpected free time to work through photographs of the mountains in order to expand the range of archaeology and history talks, including Alpine heritage, which I offer to community and special interest groups. This has provided an opportunity to reflect on examples of interpretation I have seen in museums and places I have visited. Many of the themes, contexts and challenges are relevant to those of us working with rural heritage in England including the nature of dispersed communities, small museums and the conflicting demands of conservation, public access, tourism and sustainable economic development for local communities.

Culture and Wilderness

My wife and I spend most summer holidays in the Alps, often walking at high altitude where coniferous forests and alpine meadows give way to ice, rock and snow. Museums and heritage sites are rarely a priority when planning these trips. We usually seek them out on rest days or in wet weather. However, we are not on holiday from heritage. Every day we spend walking and marvelling at the views we are engaging with it physically, intellectually and emotionally.

The Alps fascinate me because they combine wilderness and living cultural landscapes. They are the product of shifting imagination as well as geological forces. Robert Macfarlane has vividly described the evolution of these Mountains of the Mind. In the Middle Ages they were associated with horror and the realm of dragons. To Romantic writers and landscape painters in the 18th and 19th centuries they represented immense natural beauty and encounters with the Sublime. The modern tourist industry appeals to different market segments with evocations of stunning scenery for walking and relaxation, the backdrop for cliched timeless villages or sources of adventure for adrenalin fuelled thrill seekers such as climbers and paragliders. The Alps are also cultural landscapes in the sense that they have been physically shaped over thousands of years by human activities such as farming, mining and quarrying. The mountains have rarely been simply a remote wilderness inhabited by small isolated communities. For centuries they were the crossroads of Europe, traversed by Celts, Romans, Barbarians and medieval pilgrims and merchants, young gentlemen taking the Grand Tour, farmers, industrial workers and armies.

In the last few decades a growing number of museums and heritage initiatives have been established to conserve and interpret these cultural landscapes and their tangible and intangible heritage. One of the most memorable was among the smallest and most remote exhibitions we have ever encountered.

‘Pfitscherjoch Borderless’

in Austria. We chanced upon it when we acclimatised on the first day of our holiday with an easy 14 kilometre walk which climbs 500 metres to the Pfitscherjoch pass at 2280 metres on the border with Italy and then returns by the same path. The walk starts at the Schlegeis reservoir whose turquoise water is fed by meltwater streams from the Zillertal Glaciers. The route follows a stream as it climbs gently through alpine meadows and then rises more steeply over stony ground towards the pass from which it drops down the Italian side to the Pfitscherjoch Mountain Hut.

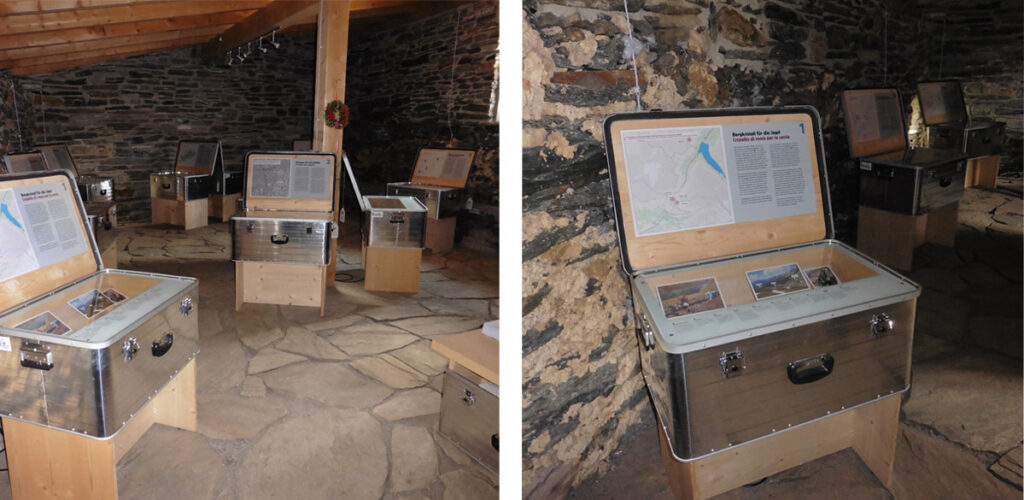

On the way down we stopped at the exhibition which is accommodated at Lavitzalm. Alm is German for a high alpine seasonal pasture up to which cattle and sheep are driven for summer grazing, milking and cheesemaking. This process of transhumance has been practised since at least the Middle Ages. Lavitzalm is still a working seasonal farm which also provides refreshments and accommodation. There is no entry fee for the exhibition which is housed in a renovated farm building. The exhibition consists of a small number of opened packing cases containing artefacts protected by glass covers with interpretive text on the inside of the lid. It tells the story of work in the mountains since prehistoric hunters first mined rock crystals to manufacture the blades and arrowheads on display. Other topics include the way local soapstone was turned into pots on the Lavitzalm in the Middle Ages and the use of the pass as a smuggling route linking North and South Tyrol. Visitors also learn about evidence for 20th century political divisions such as a mine built by forced labourers in World War II and how the Pfitscherjoch Hut was bombed by South Tyrolean separatists in the 1960s.

The museum is informed by multidisciplinary research undertaken by the University of Innsbruck. It is appealing and effective because it conveys the significance of complex academic research in a simple and imaginative way. Messages are layered to suit the audiences’ different levels of prior knowledge and interest. Interpretive text is trilingual using German and Italian on the cases and a booklet containing the English translation. There is also a pack of 16 mini booklets in all three languages exploring topics in greater detail including farming, tourism, reservoir construction and land management. All the booklets are free and can read on site or taken away as souvenirs to be reflected on at leisure.

The exhibition is low tech, gimmick free and easy to maintain. The packing cases serve as robust display cabinets and reinforce the key theme that goods have been transported over the pass for centuries. The cases and their integrated lighting system are also designed to be portable. When the Lavitzalm closes for winter the exhibition tours local communities across the Tyrol region of Austria and Italy.

There are lessons here for how we use archaeological material and touring exhibitions to interpret English cultural landscapes for visitors and residents. So often curatorial practices demand that artefacts from cultural landscapes are exhibited outside their immediate contexts in town and village museums. There are often good conservation and security reasons for this but I sometimes think we fetishize these practices. I love the way the exhibition has been crafted to reflect transhumance and patterns of movement across the mountains so that archaeological artefacts can be displayed and interpreted in situ for tourists in summer and moved in the winter through the cultural landscape and communities which they represent and in which they are rooted.

About the Writer: Andrew Thompson

Andrew Thompson is a freelance heritage consultant. His recent projects include interpretation planning and NHLF applications for the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site’s Tavistock Guildhall Gateway Project and the Looe Valley cycling trails in Cornwall. He is the South West Fed’s Hon Meeting Secretary (Conference) and a Visiting Fellow at the University of Plymouth.

All text and images copyright Andrew Thompson.